November 14, 2009 Faster Times Interview with Palestinian Author Ghada Karmi

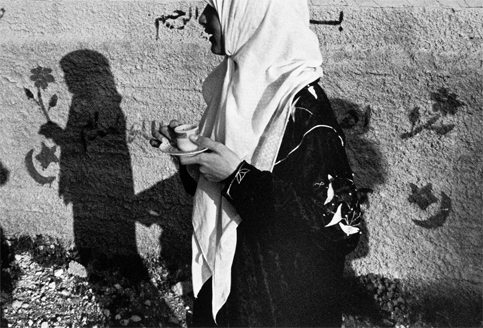

- Photo: Larry Towell Palestinian women in occupied Palestine.

Ghada Karmi is a Palestinian physician and author based in London. Since her autobiography In Search of Fatima: A Palestinian Story was first published in 2002 by Verso Books, it has been translated into forty languages. The late Edward Said described the memoir as “…the story of a fascinating woman…humanly rich and interesting.” On a speaking tour throughout the US to promote the newly-released second edition of In Search for Fatima, Mrs. Karmi visited Columbia University at the behest of an Arab cultural group, Turath. While there, she sat down with TFT associate editor Aseel Najib to discuss her wok.

Q: Did your parents encourage your literary appetite?

A: I was encouraged to read by my father, Hasan, even as a child. But not directly. He encouraged me, rather, by example. He was an expert in Arabic language and literature, and had a wide interest in many subjects: philosophy, religion, politics, history. Our home in Palestine, and later, our home in London, was full of books in English and in Arabic. I remember once he gave me a book as a present. He had inscribed its front cover. From one book lover to another, it said. I drank that in as a young girl.

Q: How, then, did you come to write a book like In Search of Fatima?

A: To be quite honest, I did not think I would write a book like this one at all. For forty years, I read literary works. But my impetus in writing In Search of Fatima was not literary; it was political. Consciously political, you could say. I think it stemmed from my understanding of the tremendous effect the Holocaust had on the Jews, and of how narrative literature was used to then convey that effect to non-Jews. I felt very strongly that our story, the Palestinian story, should be told as well, and I saw literature and writing as the appropriate means by which to tell it.

That was my intent when I began to write In Search of Fatima. But as the book began to take its physical form – that is, as I added pages and chapters to the book, it began to take on a life of its own. I discovered, while writing it that it could not be the “Palestinians’ Story”; it had to be my own. I needed, emotionally, to be able to tell that story. I needed to be able to put it down in writing, share it with the world and explain the Palestinian experience not as an ideological or political one, but as a personal one. The book became an unintended novel. As you can see, really, I ended up with something rather different than what I had planned.

Q: How do you think the realms of politics and literature interact?

A: I think that is a very good question. To answer it honestly, I have to rely on personal experience. I grew up with a love for literature, but one that lacked a political context. I think this apathy stemmed from the attitude my parents had toward the events of 1948. It was as though, after being forced to flee their homeland, they decided it was best to get on with their lives and raise their children in a normal, meaning ‘apolitical’, environment. The result was that I grew up without an awareness of those events.

My political awakening came about in the wake of the 1967 Arab Israeli War. I was in my twenties, a young doctor. I believed myself a Londoner by all standards, and the war came as a tremendous shock for me. Now, in the language of the youthful, I knew that I was on the “Arab side.” My friends, on the other hand, were on in the “Israeli side,” and this split created a process of doubt, self-questioning and reflection.

It was then that I realized: I am not an ordinary young doctor. I cannot lie to myself and pretend that I bear no larger connection to this war, to the Palestinians being killed on the other side of the globe in this war. At that point, I accepted the responsibility of being a Palestinian, and the burden of identifying with the Palestinian cause. It is not merely a self-indulgent sadness; it is a compulsion to act for that cause. To be an activist, as they say. I have remained as such throughout the years.

People may find this difficult to understand. But living through the sadness of exile – and by exile I do not only imply physical disconnection from one’s homeland, but also emotional disconnection from a larger identity – makes it impossible to forget. For most Palestinians, there is no escape. That is why it is difficult to separate my political leanings from my literary inclinations. I do not believe I can produce literature that does not bear a larger connection to the Palestinian narrative.

Q: To what extent do you think writing can be used a means of resistance and protest?

A: Very generally, I think that art, in all its forms, is absolutely necessary in the fight against annihilation. In fact, one of the most pernicious effects of Israel was the systematic and deliberate destruction of Palestinian literature, culture and history. Those are all such vital components of a national identity that their destruction is endlessly more dangerous than the demolition of homes or the establishment of roadblocks may be. The arts, I feel, can fill certain gaps; they can create consciousness, instigate discussions, bring awareness. Sadly, it took Palestinians quite some time before they understood this and began to resist in a measured, appropriate manner. Before they began to paint, write and create their own works as an impetus to realize, remember and recognize themselves as Palestinians.

Q: Yes, but it is also important to note that what art can do is paint “Palestine” in an ideological, abstract light so that it loses its actual physical dimensions, and becomes an unreachable Eden, of sorts.

A: Oh, absolutely. And this process you speak of, by which Palestine becomes some dream-like notion, is exactly what Israel would like to see. After all, a few people running around with an idea can’t do Israel much harm. What the world must do is think of Palestine as actual land; it is very much real and existent. It may not be in Palestinian ownership, but it hasn’t gone anywhere. Palestine can and should be the subject of art and literature, but that should be rooted first and foremost in its physicality. It is very much a national struggle, but not in the taking-up-arms sense that most people get when I use the term. Rather, I mean that we must struggle to remember, and to remind ourselves always of the forced exile of Palestinians sixty years ago, and of the deplorable conditions that Palestinians living in the Occupied Territories today are still made to live under.

Q: What role can women play in this “struggle”?

A: Again, this is such a loaded question I think I can only answer it according to the dictates of my memories and experiences. Personally, I think it is our collective responsibility to protest and resist Israel’s actions in Palestine. It is not solely the responsibility of women, or of Palestinians, but the responsibility of each and every global citizen who believes in the basic human rights and dignity of all people, everywhere. Everyone really must join this struggle using the capacity that he or she has been given.

I always saw myself as a writer, first and foremost, and have attempted to use that ability to further the Palestinian cause. That said, I think my gender did not matter very much when I published In Search of Fatima. If anything, my being a woman may have made the book more accessible and appealing to all readers. But bear in mind that I was writing as an Arab woman in the West, and that I was writing the book for a largely western audience.

Q: Would things have been different, do you think, had you published it in the Middle East?

A: Well, if I were living in the Arab world, I think things would have been very different. Having taught for a number of years in more than one Middle Eastern university, I think it is fair for me to say that Arab women face a number of difficulties in making their voices heard. And it is interesting that in most cases, the discrimination they face does not come in the form of censorship, preclusion or exclusion. It is much worse from that. What most Arab female writers and thinkers face in the Middle East is marginalization. They are dismissed, overlooked, cast aside and made to feel that they-and their work-are unimportant and insignificant.

And personally, this marginalization would have defeated the spirit of In Search of Fatima. The book is about putting forth an essentially Palestinian voice rarely heard on the literary scene. Part of its importance stems from its uniqueness. And in the Arab world, women are made to feel as though their experiences are not unique or important. They are made to feel as though their experiences are banal, trivial and uninteresting. This contradiction is why I could never have published In Search of Fatima in the Arab World.

Interestingly enough, the book is currently being translated into Arabic. It strikes me as strange that this is happening just now; a book such as In Search of Fatima, in my opinion, should have been translated into Arabic years ago. It has occurred to me that my being a woman may have had something to do with the delay. You really do never know.

Q: In your opinion, how can women in the Middle East, and particularly in Palestine, make their voices – literary and otherwise – heard?

A: The answer I can offer is, simply: they will have to persist in their excellence. It is a step-by-step process. Women must first produce incredible work. They must continue to push the envelope in their writing. Good writing can only be ignored for so long. Excellent writing really cannot be ignored at all, especially not in today’s day and age when women have technological access that can help them “get their work out there”, as my editor used to say.

They must next believe in, and insist on, the excellence of their work. It is easy to be put off; it is easy to feel daunted, dejected or uninspired. But emotions such as these are really the cowards’ way out. Women must go on writing and confronting the prejudices against them. They can even do both at once! Women can confront those prejudices through their writing. But really, they truly must agitate, argue and make a clamor. And this is something we must all learn- as women, as Palestinians, as writers: we cannot be self-conscious in saying what we are compelled to say. We each have a valid point of view; we have every right to make it heard, even if we must shout it from the rooftops.

Q: Some women would argue that they do not write because an audience does not exist for their work.

A: I used to believe that I needed an audience of the “other” in order to feel as though I had achieved my goal. That in my lectures, in my book readings and signings, I needed to convert people to the Palestinian cause. Now, however, I do not wish to speak to the jaded, to the Zionist, to the uninterested. I’ve realized that I need to focus on the younger generation of activists who witness and protest Israel’s utter disregard for the basic human rights of Palestinians. I feel as though this educated, enthusiastic group could use some sort of direction – and I feel as though my generation has much to offer them. Mind you, this shift in my targeted audience has come about after years and years of activism on my part.

So, this question of, who will listen to me? is completely irrelevant and ultimately useless. It is also very sad. It is a way of giving into history and to power. A way of giving up before you have even begun and writing yourself off for fear that others will write you off.

Simply put, it is not a writer’s responsibility to choose who will read her work, or who will be affected by her words. It is up to her to tell her story. I would say to Palestinians, women and writers everywhere: write and leave behind your own truth; it will take care of itself.